#16 - India’s EV capital won’t be Made in India

At least not for now

Hello and welcome to this week’s edition of Lights On, a newsletter that brings you the key stories and exclusive intel on energy and climate change in South Asia.

Round of applause to all new subscribers, if you enjoy hearing from me please share this newsletter with friends and family. And if you haven’t signed up yet, now is your chance, I also send a Monday email where trawl the news so you don’t have to:

Big promises

- Delhi has a new ambitious EV policy to help add half a million vehicles to its electric fleet

- It does away with the protectionist measures that have crippled previous EV schemes

Delhi is the most polluted capital city in the world, but it wants to swap this title with that of India’s electric vehicle (EV) capital. Last week, the chief minister Arvind Kejrival introduced a new incentive package to help put 500,000 new such vehicles on the road by 2024.

If successful, this fleet will save 4.8 million tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions over their lifetime - equivalent to just over a million conventional cars driven for a year.

The Delhi Electric Vehicle Policy 2020 has been hailed as a model for other states that so far have failed to realise the ‘EV revolution’ they were hoping for. Unlike many other policies, which have tried to attract investments by incentivising makers and sellers, the Delhi scheme is focused squarely on encouraging more drivers to go electric, and wait for businesses to respond. It offers a flurry of generous incentives. Those who choose to scrap their internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicle will receive a bonus of up to $400 (30,000 rupees) if they purchase an electric motorbike, scooter or auto-rickshaw. The first 1,000 drivers who take the plunge after this week will be eligible for up to $2,000 (150,000 rupees) against a new electric car.

To finance these and other perks, as well as the creation of a denser charging network and, down the line, battery recycling facilities, Delhi has established a special fund financed by the existing air ambience fund and additional taxes on polluting vehicles.

Even if this policy delivers on its promises, Delhi is only one of the many critically polluted Indian cities that would benefit from replacing as many ICE cars as possible. But it has learned from mistakes that have tanked nationwide attempts to scale up electric mobility.

Own goals

The existing national policy for Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Electric Vehicles (FAME), whose second phase kicked in in April 2019 with a budget of $1.4 billion (100 billion rupees), offered similar incentives to drivers contemplating the green option - with a catch: within just 18 months from the launch, all components should be made in India.

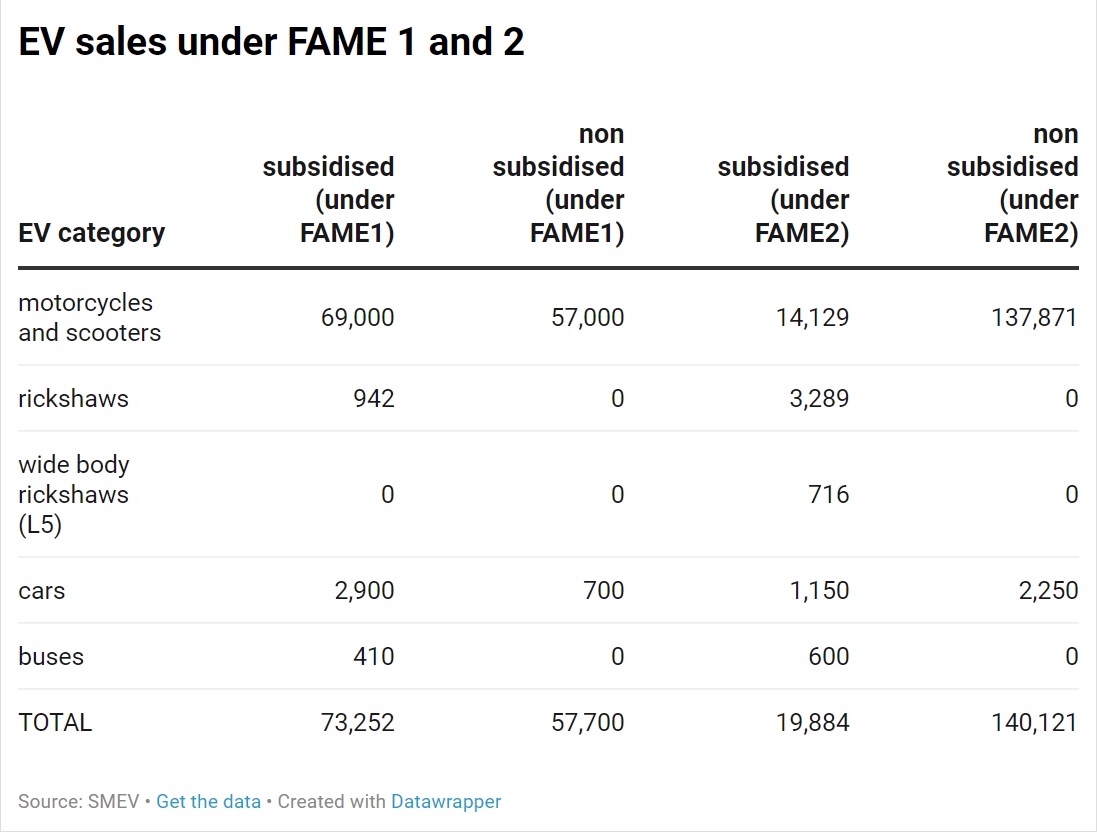

While this was meant to encourage local EV manufacturers, it had a chilling effect on sales instead. Under the FAME 2 scheme, when localisation was made mandatory, the number of subsidised vehicles collapsed from 73,252 to just short of 20,000.

This is because the vast majority of EV parts are still produced abroad - and in news that will surprise no one - they largely come from China. Look at the 1.5 million electric rickshaws on India’s roads, a disgruntled manufacturer tells me - despite a boom over the last seven years, about 70 percent of parts are still imported from China. “Clearly government incentives are directly benefiting Chinese manufacturers most,” he says.

And if you slam the brakes on imports, people may simply stop buying because while manufacturers scramble to fill the gap there will be nothing for consumers on the market, at least for a few years. Industry and government are not seeing eye to eye on how to put the first few million electric vehicles onto the roads of the most polluted cities, says Sohinder Gill, director general of the industry group Society of Manufacturers of Electric Vehicles (SMEV). “If we can start a critical mass, people will start talking to each other about the benefit of electric mobility.” Once a sizable demand is created, local manufacturers will see the sector’s promises “and the rest will follow,” Gill says.

A global race

Some believe it may be too late for India to get ahead of the game on the production of key components such as lithium ion batteries, which have a much higher energy density and charge faster than the conventional lead acid ones. India announced its National Mission on Transformative Mobility and Battery Storage in March 2019, but to date “there is no dedicated funding under that mission to give early incentives to battery storage,” says Anup Bandivadekar, India lead with the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) in San Francisco.

“The longer India waits to move on this one, the harder it's going to be for domestically made batteries to be cost competitive,” he tells me. “We are already seeing hundreds of gigawatt hours of battery capacity plans being announced all over the world. And essentially, you're now competing with everybody, not just with Chinese manufacturers.”

A protectionist approach on manufacturing has been giving headaches to solar developers for years, and has yet to help Indian solar makers. Electric mobility is still a young industry, but the window for India to get ahead of the game is rapidly closing - and imposing draconian restrictions on its development may as well stifle its development.

Climate change is a global issue, and energy transition is a race with no borders. If India wants to tap into that opportunity when it comes to EV, it will have to rethink its interpretation of self reliance. Perhaps, Delhi’s new policy is a first step in that direction.

If you’ve been forwarded this newsletter and you’d like to read it every week, you can subscribe below. Tip: if you add my address to your contacts, this email won’t end up in the spam or promotion folder!