#9 - The cost of a trade war

Solar energy prices just hit a new low in India. But the good times may not last.

Hello and welcome to this week’s edition of Lights On, a newsletter that brings you the key stories and exclusive intel on energy and climate change in South Asia.

While the newsletter is still completely free, you can support me with a small donation here. I’ll be very grateful!

India at the crossroads

- Despite the post-Covid crisis, Indian solar still thrives and prices keep falling

- A trade war with China may throw a spanner in the works

Solar energy prices just hit a new record low in India!

And so soon after a previous project promising the lowest tariffs around was canceled due to the coronavirus crisis.

To win the right to build 2GW of new capacity, Spain’s Solarpack offered 2.36 rupees ($0.03) per kilowatt hour, while the previous lowest tariff was 2.44 rupees per unit. Sounds great, right?

Look closer. While it’s true that the lockdown couldn’t kill the solar momentum - a looming trade war with China may do just that.

The bright future of Indian solar

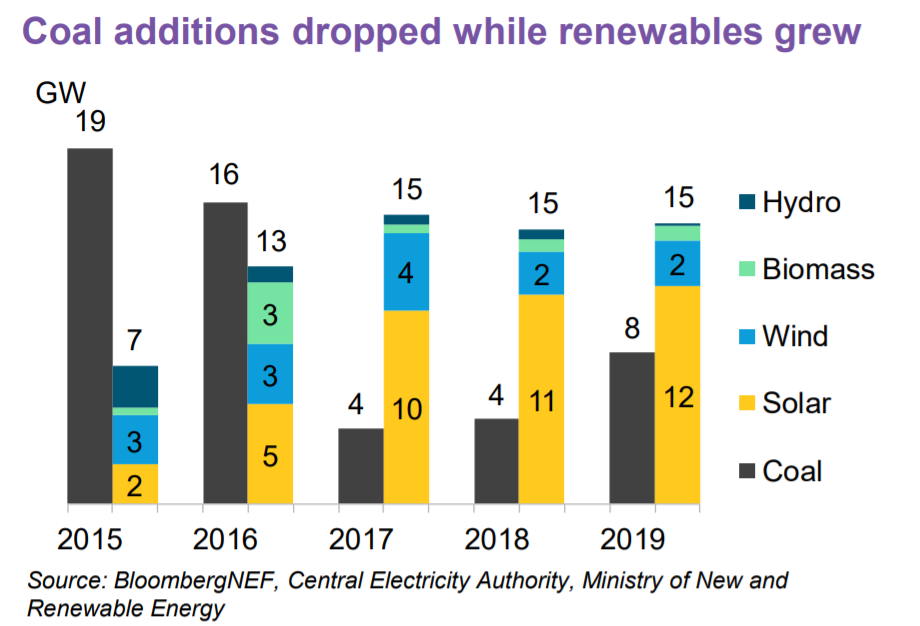

According to the intelligence service BNEF, India is now the most attractive emerging market for clean energy, thanks to the world’s biggest auction market where developers compete to deliver the cheapest possible power. This system has helped shift the balance between solar and coal in new capacity - now India adds much more renewables than coal to its energy mix every year, while just 5 years ago coal installations were nearly double that of all renewable sources combined.

Renewable power is cheaper too: thermal power currently costs about 3.60 rupees ($0.05) per unit. In just a decade, India’s wind and solar capacity quadrupled, and in 2019 it reached a cumulative 82GW.

But here’s the problem. India has also set impossibly high targets for itself. Prime Minister Narendra Modi promised to reach a total of 175 GW by 2022. This would mean adding another 93GW of capacity to the fleet in one and a half years.

Confusingly, instead of adjusting ambitions, the PM doubled down and increased renewable targets from 400 to 450GW by 2030. But that’s fine. Targets can be aspirational. Here in India the fact that they won’t be met is an open secret, but they are generally seen as a sign that India is serious about clean energy and there is space for investment.

Harm China at any cost

What the government doesn’t seem to notice, while caught up in an anti-China campaign that most analysts agree is not good for the Indian economy, is that solar progress has been riding on falling technology prices. In the last quarter of 2019, 85 percent of solar modules and cells used in India came from China.

As we saw earlier this week, the government retaliated after the death of 20 Indian soldiers during a border standoff by imposing a series of economic measures aimed at penalising China. Among them, the Power Ministry had originally announced a 40 percent custom duty on imported solar modules, 25 percent on solar cells and 20 percent on inverters by 2022 starting from August.

No one feels comfortable saying this out loud, partially because India is really hating China right now, and partially because reducing imports and increasing manufacturing is part of the ‘Self Reliant India’ recovery strategy laid out by PM Modi.

But backstage, the industry is in disarray. Cranking up the price of Chinese panels over such a short period of time means that developers lose access to cheap and *state of the art* equipment. A senior source tells me that even if importing from China is a nightmare at the best of times, developers still go for it because the quality of the panels is better.

So, imposing custom duties will end up promoting sub standard panels. At the moment, the best Indian manufacturers can do are modules with 360 watt peak (Wp), the maximum electrical capacity of a panel when under a cloudless sky and facing the sun. But the market standard demands 400Wp, and earlier this year two Chinese manufacturers have unveiled a super efficient 500Wp model.

If inefficient modules become the standard in India, ultimately consumers will pay the price.

A tough race

Industry associations are now scrambling to shield what’s already in the pipeline, and asked the ministry to grant an exemption for projects worth 29GW. Subrahmanyam Pulipaka, CEO of the National Solar Energy Federation of India, tells me that these are particularly vulnerable because developers had not envisaged the price hike when bidding. “We have provided a list of around 110 projects with their date of import and commissioning to the ministry last week, and the government seems receptive,” he says.

Arunabha Ghosh, CEO of the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) in Delhi has a counterpoint. While he is not advocating for a ban on solar imports, which helped drive the industry’s growth, “there is no doubt if we are looking at [a target of] 450GW of renewable capacity we have to build up the domestic capacity to have a substantial share of that.” That would also mean saving more than a billion dollars a year in imported panels, he adds.

In an ideal world, this tough time would be a golden opportunity for India to put a lot of effort into producing more and better solar panels: foreign investors are flocking in, the 2022 deadline approaches and the government is throwing its weight behind the plan. But in reality there is very little chance that India will be able to become the pro solar maker Modi wants it to be in just a couple of years.

And with climate change breaking new frightening records every month, a trade war crippling the progress of a solar powerhouse such as India is the last thing the world needs.

If you’ve been forwarded this newsletter and you’d like to read it every week, you can subscribe below. Tip: if you add my address to your contacts, this email won’t end up in the spam or promotion folder!