Revealed: The catch behind China's international mega-loans

And how it could set back efforts to decarbonise its foreign investments

Welcome to today’s Lights On, a newsletter that brings you the key stories and exclusive intel on energy and climate change in South Asia.

In case you missed them, head back to my analysis of a potential net zero target for India, and my weekend Q&A on why regional cooperation could make or break India’s energy transition goals.

If you are not a subscriber, you can sign up below, for free, or you can support my work by purchasing a membership:

For more than a decade, China has been helping poor nations grow. The world's largest official creditor, China has focussed its lending on Africa, Asia and Latin America, spending billions financing projects such as roads, communication infrastructure, power plants and more.

But as China’s financial influence expands, and the world starts to pay more attention to how the money is spent, there is still little clarity on the strings attached to it. The conditions behind a loan, especially as big as the ones China offers to developing countries, can influence the recipient’s domestic and foreign policies. And when it comes to facing scrutiny for its carbon intensive investments abroad, a lack of transparency may taint the country’s efforts to build its reputation as a climate leader.

Now a first of its kind project has compiled a portfolio of 100 confidential loan agreements between Chinese institutions and 24 governments across the developing world, mostly in Africa and Latin America.

It reveals for the first time the sweeping and sometimes unusual clauses China imposes on beneficiary countries to expand its soft power.

Loans with strings attached

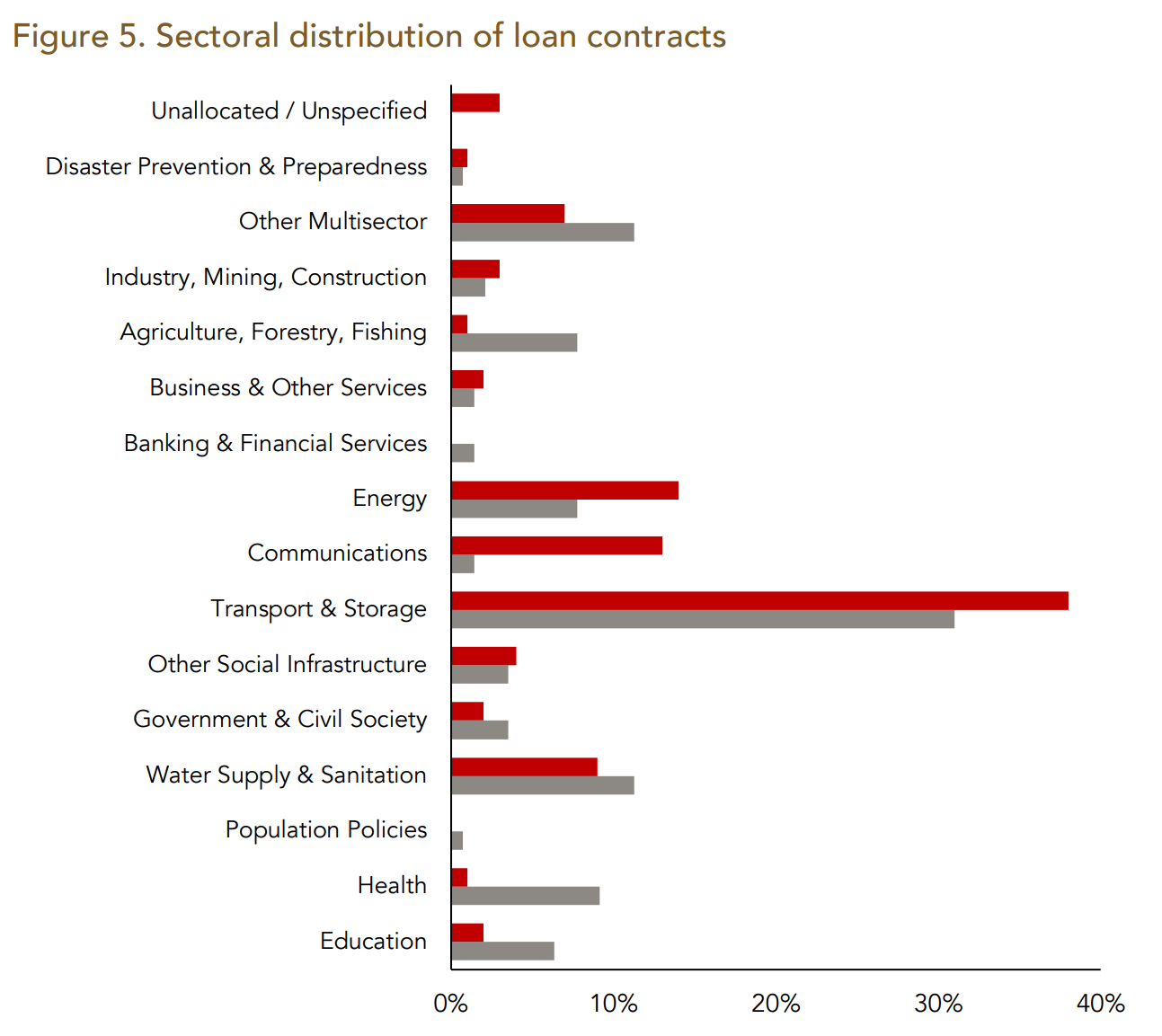

Energy and transport are the top two sectors receiving finance in the new documents. Of 23 energy contracts, 18 are for fossil fuel based or hydropower projects. The 78 documents classified under transport and storage include the construction of highways, ports, railways and other carbon intensive infrastructure. China has signed about 2,000 deals with the developing world to date, but most of them remain shrouded in secrecy.

Armed with a unique sample of documents scraped from gazettes, parliamentary websites and other official sources, researchers at four international institutions worked out the standard template for most of these deals - including a series of problematic clauses.

Among these is a confidentiality requirement found in most of the contracts that prevents the recipient from revealing the terms, or even the existence, of the debt.

Things get a little more complicated where Chinese lenders ask recipient governments to set up, or work with, friendly banks that will act as guarantors in case the debt is not repaid. The recipient will have to put all revenues from the Chinese funded projects in this bank, where they are effectively kept out of the country’s control.

The two clauses combined make it difficult to monitor whether a country is in too much debt, and the financial flows associated with foreign lending.

“It's unclear whether a country really wants to have its debt stuck out in the public,” says Sebastian Horn, economist at the Kiel Institute for the World Economy in Germany and one of the authors of the research. “There might be an incentive to underreport debt just in order to get better conditions from the international market, not showing signs of debt distress to avoid higher lending premiums from other creditors.”

But from the creditor perspective, the motivation seems less clear. “If a creditor is financing a large infrastructure energy project, it should actually have an incentive to put that on its website and say, look, we're investing in these countries and doing a lot of good.” Confidentiality clauses make little sense, Horn says, because they raise distrust on the international markets, and make debt restructuring much more challenging.

In addition to the unusual confidentiality requirements, nearly all deals stipulate that the contract can be immediately terminated, and the loan repaid, if the recipient country implements new policies relevant to the projects funded, or takes any actions adverse to the interests of “a Chinese entity”.

Policy disconnect

“This database makes it clear the mechanisms through which China exerts influence in host countries,” says Cecilia Han Springer, a senior researcher at the Global China Initiative within the Global Development Policy Centre at Boston University.

Han Springer, who tracks Chinese investment in the power sector, explains that “the Chinese actors responsible for setting debt contracts are not the same ones who regulate or monitor potential environmental impacts.” This shows that there should be more policy integration at the China Development Bank and Export-Import Bank of China regarding how their loans are carried out, “not leaving oversight and environmental impact assessment for later, or to external actors,” she says.

Green lending, she adds, needs to be incorporated into initial lending decisions and terms, because there is a strong link between sustainable finance and environmental sustainability, something that Chinese lenders have yet to recognise or act upon. China's regulatory approach focuses more on projects that are already underway, and will be much harder to decarbonise, rather than on the initial project design and approval. “To implement greener lending, there will have to be scrutiny at all stages,” Han Springer says.

Lessons for South Asia

The researchers say that Asia is likely under-represented in the sample, but they say that the contract template is unlikely to vary significantly between regions. In fact, the report says, it tends to depend on the type of lending instrument and the identity of the creditor.

Despite the scarce documentation about the region, Han Springer says that countries in South Asia that are already doing business with China can learn from this study too. “In the power generation sector, Bangladesh and Pakistan are facing a glut of Chinese investment and potential overcapacity - recent project cancellations may reflect mistrust of Chinese lending practices and a desire to move away from fossil fuels,” she says. “These countries can advocate for better lending terms for the still much-needed capital for cleaner energy sources; there could also be lessons for courting more transparent loans from regional developers - namely India - in a ‘race to the top’.”

That’s all for today! If you like what you read, please consider signing up for free or as a member: